Computational Thinking

Scams in the Digital Age: A Survival Guide

Visit Paul's websites:

From Computing to Computational Thinking (computize.org)

Becoming a Computational Thinker: Success in the Digital Age (computize.org/CTer)

Scams in the Digital Age: A Survival Guide

In an earlier article on Objectivity, we emphasized the value of staying calm, collected, and attentive to details. These qualities allow us to see situations clearly instead of emotionally. In the digital age, objectivity is not just good practice—it is a powerful defense against scams.

Modern scams are no longer isolated tricks. They are global, technology-driven opera-tions that rely on automation, stolen data, psychological manipulation, and even artificial intelligence. In the U.S., the average person receives about 30 scam attempts each week. Scammers trick you into rushed emotional reactions so as to steal your money, property, assets, personal information and even your identity. By applying Computational Thinking (CT) and practicing objectivity, we can neutralize their evil plots and avoid becoming victims.

This article provides (1) a set of realistic cases showing how scams have evolved, (2) preparedness strategies that build mental immunity, and (3) a simple emergency action plan—a kind of “antiscam penicillin”—for dealing with suspicious calls or messages. This

article is part of our ongoing CT blog published in aroundKent, an online magazine. Other enjoyable and engaging CT articles can also be found in the author’s book Becoming A Computational Thinker: Success in the Digital Age.

How Scams Have Evolved: A Timeline

Scams evolve rapidly, much like software updates. Below are realistic case summaries placed in chronological order.

2004, Cleveland, Ohio — Bank Verification Email Scam

Mark, 32, received a bank email with realistic logos and a link to a fake login page. In the morning rush, he entered his password. $3,800 was withdrawn before he realized. The phishing ring was never found.

2012, Fresno, California — Tech-Support Pop-Up Scam

Linda, 68, saw a pop-up claiming her computer was infected. A fake “Microsoft technician” took remote control, sold her a “protection plan,” and stole card information—total loss: $2,700. Fear and confusion overrode her objectivity.

2019, Plano, Texas — IRS Robocall Scam

Mr. Williams, 74, was told he owed back taxes and faced arrest. In panic, he bought

$4,000 in gift cards and read the numbers to the scammer. Local police confirmed the scam; perpetrators operated overseas.

2022, Seattle, Washington — “Pig Butchering” Scam

Emily, 45, developed a two-month online relationship with “Daniel.” He guided her to a fake crypto platform. She invested $61,000; the site vanished. The scam was traced to a forced-labor compound in Cambodia.

2023, Phoenix, Arizona — Voice-Cloning Kidnapping Scam

Maria, 52, received a call with a cloned audio of her daughter’s voice crying for help. A ransom was demanded. She verified by calling her daughter’s real number. The scammers used a disposable VoIP line.

2024–2025, San Diego, California — Deepfake Video Scam

David, 38, joined a video call showing deepfake versions of his CFO and executives. Believing their “strategic acquisition” story, he authorized a $2.6M transfer. Only later was the fraud uncovered. This exposed the new frontier of AI-powered impersonation.

Scams Are A Serious Problem

The preceding incidents do not begin to describe the extent and scope of the problem. The average American receives around 25-28 scam calls/texts/emails combined per week, totaling about 100 monthly, making the U.S. a global leader in scam attempts, with many adults getting these daily, according to the Pew Research Center and CNET.

Scam losses worldwide surpassed US$1.03 trillion in 2024, according to the Global Anti-Scam Alliance (GASA). The organization also found that nearly half of consumers encounter scam attempts at least weekly–and among those who fall victim, only 4% fully recover their money. In the US the losses in 2024 exceeded $16.6 billion according to the FBI. Worse yet, wide-spread scamming erodes public trust in messages and notices from individuals, businesses and governments. Such loss is immeasurable.

The Causes? A CT View

From a CT perspective, scams thrive because of:

- Automation: Millions of attempts at negligible cost.

- Global networking: The Internet, Web, mobile phone networks provide unprecedented speed and reach.

- Stolen data: Personal information enhances plausibility.

- Psychology: Using technology to exploit fear, urgency, and trust.

- Jurisdiction gaps: Criminal rings operate beyond local reach.

Scammers are also increasingly using fast, AI-powered A/B testing (split testing) to rapidly figure out which messages, emotional tactics, or hooks work best to trick people, allowing them to scale successful scam scripts and create highly effective, personalized fraud funnels. They test different greetings, urgency levels, or emotional appeals on small groups, quickly identifying high-converting pitches to deploy broadly, making scams more convincing and efficient.

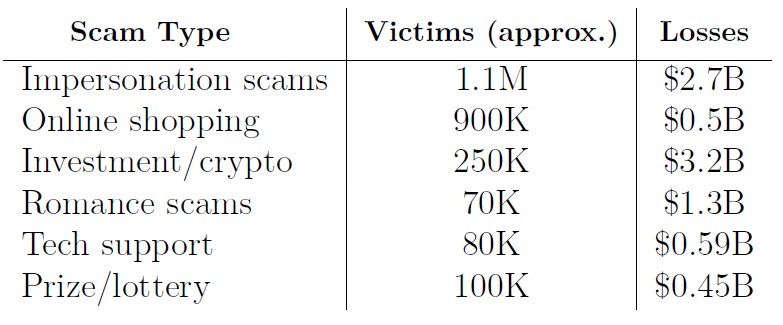

Here is a table showing the most common scam categories:

From Small Cons to Global Frauds

Most people think of scams as small tricks—phishing, fake tech support, romance scams. But scams exist on a wide spectrum, from low-dollar personal frauds to multi-billion-dollar

institutional deceptions. Understanding this landscape clarifies that all scams, regardless of scale, exploit the same underlying vulnerabilities: emotion, trust, complexity, and the lack of independent verification.

Scam Dimensions

Scams can be analyzed across three conceptual dimensions:

Scale of Impact

Mechanism of Deception Across all scales, scams use similar cognitive exploits:

- Psychological manipulation (fear, urgency, trust, greed)

- Information asymmetry (hidden processes, unverifiable claims)

- Manufactured credibility (fake authority, fake science, fake results)

- Complexity shields (financial jargon, scientific claims, legal structures)

- Social proof engineering (fake endorsements, accomplices, shills, insider legitimacy)

Domain of Operation Common scam domains include:

- Financial scams: Ponzi schemes, pump-and-dump, insider fakes

- Scientific/medical deception: fraudulent datasets, miracle cures, Theranos

- Corporate/institutional fraud: Enron accounting, VW emissions cheating

- Government/propaganda deception: fake news factories, political bots

- Everyday online fraud: phishing, identity theft, fake storefronts

Snapshots of Major Large-Scale Scams

A few actual examples of big scams can put things in context. Even prestigious institutions, seasoned investors, and scientific experts can be misled when objectivity breaks down. Below are brief summaries of some major scams that made headlines worldwide.

Bernie Madoff Ponzi Scheme (1980s–2008): Madoff, a respected Wall Street figure and former NASDAQ chairman, promised steady, market-beating returns. He fabricated account statements showing consistent profits, even during market downturns. Investors trusted him because of his reputation and exclusivity. In reality, no trading occurred; new investor money was used to pay earlier investors. The scheme collapsed in 2008, revealing an estimated $65 billion in paper losses.

Theranos and the “One Drop of Blood” Claim (2003–2018): Theranos, founded by Elizabeth Holmes, claimed to perform hundreds of laboratory tests from a single finger-prick of blood. The technology never worked, but carefully staged demonstrations, secrecy framed as innovation, and endorsements from generals and former Secretaries of State created an aura of legitimacy. Walgreens invested heavily and planned nationwide rollout. Investigative reporting eventually exposed the deception; the company collapsed and its leadership was convicted of fraud.

Volkswagen Emissions Scandal (2009–2015): Volkswagen programmed diesel engines to detect laboratory testing conditions and temporarily alter emissions performance, passing environmental tests while emitting far higher pollution on the road. Consumers, regulators, and environmental groups were misled by the brand’s engineering reputation. The scandal triggered global recalls, billions in fines, and criminal charges.

FTX and Alameda Research Collapse (2019–2022): FTX, one of the world’s largest cryptocurrency exchanges, portrayed itself as a secure and transparent platform. Behind the scenes, customer funds were secretly funneled to Alameda Research for risky trades, while the company generated fake balance sheets to appear solvent. Charismatic leadership, celebrity endorsements, and crypto hype created a powerful illusion of stability. When the truth surfaced, more than $8 billion in customer assets were missing.

A Global Pattern of Deception

Large-scale scams are not limited to the United States. Around the world, major cases in science, finance, and corporate governance illustrate that deception follows universal cognitive and structural patterns. The same vulnerabilities exploited in everyday scams—trust, authority bias, lack of verification, social proof—also enable billion-dollar institutional frauds.

- Prince Group (Cambodian, 2015–2026): Created by Zhi (Vincent) Chen (陈志) in 2015 and expanded quickly internationally through 2024; alleged involvement in large-scale scams. Prosecutors say the group operated dozens of scam sites and “pig butchering”crypto and romance fraud schemes that tricked people worldwide into sending money, using trafficked and forced-labor workers held in walled compounds in Cambodia to run the scams. In 2025 the group was sanctioned, indicted, and its massive cryptocurrency (127,271 Bitcoin, valued at over $15 billion) seized by the FBI and DOJ. Chen Zhi was arrested, stripped of Cambodian citizenship in late 2025, then was extradited to China for prosecution on January 6, 2026.

- Ezubao P2P (e 租宝 peer-to-peer) Lending Scheme (China, 2014–2015): Ezubao presented itself as a trustworthy peer-to-peer lending platform promising high, stable returns. In reality, 95% of listed investment products were fabricated. Investor funds were used to pay earlier investors and to finance executive luxury purchases. With nearly 900,000 victims and losses exceeding $7.6 billion, it remains one of the largest Ponzi schemes in Chinese history.

- Hanxin Microchip Fraud (汉芯一号, China, 2003–2006): Promoted as a break-through in Chinese semiconductor technology, the “Hanxin One” chip was claimed to be an original domestic innovation. Investigations later revealed that the chips were foreign products with markings sanded off. Prestige, nationalism, and lack of repro-ducible testing allowed the fraud to persist. The case became a symbol of scientific integrity failures. (Note: Most chips have an internal unmodifiable electronic id.)

- Olympus Accounting Scandal (Japan, 1990s–2011): Olympus executives se-cretly concealed over $1.7 billion in losses for more than a decade using inflated acquisition fees and complex financial arrangements. The fraud was exposed only after a newly appointed CEO questioned suspicious transactions. The case demonstrates the dangers of internal opacity and cultural resistance to internal whistleblowing.

- STAP Cells Scientific Fraud (Japan, 2014): A widely publicized claim that pluripotent stem cells could be produced simply by acidic stress (“STAP cells”) was published in Nature. The global scientific community attempted replication and failed. Subsequent investigation found image manipulation and data fabrication. The case underscores the importance of reproducibility and verification in scientific research.

- Satyam Computer Services Accounting Fraud (India, 2009): Once a major IT firm, Satyam falsified revenues, profits, and assets to inflate its market value. The chairman eventually admitted to manipulating financial statements, causing the com-pany to be called “India’s Enron.” Over $1 billion in fictitious assets were uncovered.

Analyzing Scams

When we see scams at all scales—from phishing texts to falsified science—patterns emerge:

- All exploit the same cognitive weaknesses: fear, urgency, trust, authority, greed.

- All rely on lack of independent verification.

- All succeed when emotion overrides objectivity.

- All collapse once data-driven scrutiny and CT principles are applied.

This unified perspective reinforces a key message of this CT article series:

Objectivity and verification are universal defenses, whether dealing with a suspicious text message or a billion-dollar scientific claim.

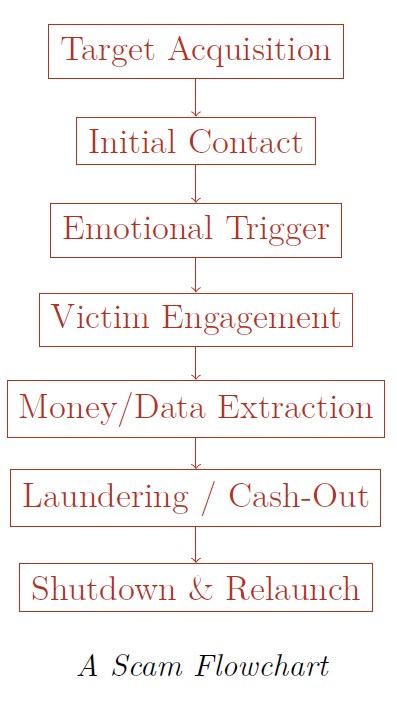

Furthermore, we can expose the plot of a typical scam to see how it works step by hideous step. By disrupting it at any intermediate step, the whole scheme falls apart.

Preparedness: Building Mental Immunity

Our goal is to get all of us ready to defend against these hideous scams, big or small. An important CT principle is to preplan for all contingencies. Here, preparedness means developing habits and rules before facing a scam attack. It converts uncertainty into confidence.

- Recognize the Three Universal Tools of Scammers: All scams, from 2000 to 2025, rely on three emotional triggers:

- Fear: “You are in trouble.”

- Urgency: “Act now or miss your chance.”

- Get Ready

- Trust or Emotion: “This is your bank…this is your boss…this is your loved one…a free grand piano…high investment return…unbelievable discount…miracle cure.”

- Preparedness means noticing these emotional sparks immediately. They should engage your objectivity in high gear.

- Pre-Decide Your Rules: People make mistakes when deciding under pressure. Precommitment restores calm thinking. Example rules:

- “I never respond directly to texts or emails asking for quick action.”

- “I never share personal information on an incoming call.”

- “I always verify using an earlier known phone number or website.”

- “I never pay via gift cards, crypto, wire transfer, or QR code under pressure.”

- These simple rules prevent emotional shortcuts.

- Prepare a Personal Verification Toolkit: Have official contact information ready—before any scam attempt:

- official bank/business phone numbers and websites,

- government agency numbers (IRS, Social Security, local police, etc.),

- employer directories,

- family contact list and rules for emergencies.

- Verification becomes effortless when your references are prepared.

- Family and Community Rules: Scammers succeed by isolating victims. Shared rules prevent this.

- “If an emergency call comes, we call each other first.”

- “No major decisions are made alone.”

- “We always verify unexpected requests.”

- Phone-Answering Strategy: A practical defensive habit:

When answering the phone, don’t state your name or identity. Just say “Hello.”

If the caller insists on confirming your name, you may reply:

“They are not available. Can I take a message?”

This preserves privacy and can frustrate any potential scammer, buys time, and gives you reason to ask who they are and their detailed contact information which you must check and verify before taking any action.

Using AI: Your Instant Scam-Check Assistant

We all can use modern technology to fight modern scams. AI is now a powerful everyday tool for restoring objectivity in moments of stress. It provides immediate, calm analysis when your emotions are triggered.

When something feels suspicious, go to your Web browser search box, or your favorite AI chatbot, and simply type:

Scam check: [short description of the situation]

Examples:

- “Scam check: Someone offered me a free grand piano but wants me to pay the mover.”

- “Scam check: Caller says my Social Security number is suspended.”

- “Scam check: My boss texted me to buy gift cards urgently.”

- “Scam check: A dating app contact wants me to invest in crypto.”

AI has seen thousands of scam patterns, government warnings, and reports. It can immediately explain red flags, restoring calm and objectivity. Provide only a brief description; do not include sensitive personal data. AI does not need full details to identify scam patterns. One day soon, you’ll be able to use voice and say “scam check ...” instead of typing.

“Antiscam Penicillin”: Your Action Plan

When receiving a suspicious call or message, you need a simple, repeatable procedure. This is our “penicillin”—a universal scam-cide ordinary people can apply instantly.

Step 1: Pause

Scammers rely on speed. Take a breath. Put the phone down. Stop typing. This reactivates your objectivity. Ask yourself “Do I know this person/organization?”, “Have I got an address or phone number to verify and to get back to them?”, “Can the story they gave be used on many others?”

Step 2: Identify the Emotional Trigger

Ask:

- Did this invoke fear?

- Did this create urgency?

- Did this impersonate someone I trust?

If yes, treat it as suspicious.

Step 3: Disengage Safely

Reply: “Will definitely contact you soon.”

Do not argue. Do not obey instructions. Just disengage.

Step 4: Verify Independently

Any and all information from a scammer can’t be trusted. Use your own prepared toolkit:

- genuine website that you used and bookmarked before,

- official government numbers,

- employer directory, known family contacts.

Never use the caller provided phone/email, attachment, link, website or app. Legitimate companies and organizations rarely demand immediate action via text/email; instead, they tell you to log into your account directly to handle any issues.

Step 5: Report and Secure

Reporting helps you and others: Contact your bank, your phone carrier, FTC or local police, and/or family and community groups. Each report strengthens collective defense.

Beyond Defense: Forming A Collective Offense

Decent People Unite to Fight Back

Scammers form organizations to victimize all of us. We must also get together to fight back. Here we propose that decent people form a united front. All of us can be the “sensors” in a well-organized nonprofit national anti-scam center (scamcide.org for example) which becomes a central reporting portal that can combine:

- FBI and law enforcement reports,

- bank fraud analytics,

- telecom spam data,

- social media abuse signals.

Such a center could issue real-time national alerts, just like the CDC.

Whistle-Blower Incentives Provide publicly announced rewards for scam whistle blowers. Criminal organizations lack loyalty. Scam insiders can supply:

- scam scripts, organization structures,

- mule accounts, money laundering channels,

- physical compound locations.

Rewards and safe reporting channels can bring down entire networks.

AI Tools for Public Protection Provide a publicly available “ScamShieldBot” or “ScamProofBot” that can:

- analyze suspicious messages,

- detect cloned voices or deepfakes,

- highlight risks in plain language,

- feed anonymized patterns into the national database,

- improve via collective feedback.

Of course, it is high time for nations to get together and declare war against global scams, their perpetrators, facilitators, and protectors, so there is no place to hide.

Conclusion

In the digital age, scams are a serious and growing problem for individuals and the whole society. Modern scams aim to disrupt our objectivity by triggering fear, urgency, or emotion. The devious techniques are ever changing and more clever as time goes by. No one is immune. But knowledge of deception patterns, preparedness, CT skills, and disciplined habits can help us immensely. The guide is simple:

Objectivity is our built-in shield.

Verification and calm attention can defeat deception.

With shared reporting, whistleblowing incentives, AI assistance, and coordinated institutional reactions, society can become significantly harder to fool. Lastly, a practical and effective anti-scam system to protect all citizens, especially vulnerable individuals, is achievable and urgently needed.

ABOUT PAUL

A Ph.D. and faculty member from MIT, Paul Wang (王 士 弘) became a Computer Science professor (Kent State University) in 1981, and served as a Director at the Institute for Computational Mathematics at Kent from 1986 to 2011. He retired in 2012 and is now professor emeritus at Kent State University.

Paul is a leading expert in Symbolic and Algebraic Computation (SAC). He has conducted over forty research projects funded by government and industry, authored many well-regarded Computer Science textbooks, most also translated into foreign languages, and released many software tools. He received the Ohio Governor's Award for University Faculty Entrepreneurship (2001). Paul supervised 14 Ph.D. and over 26 Master-degree students.

His Ph.D. dissertation, advised by Joel Moses, was on Evaluation of Definite Integrals by Symbolic Manipulation. Paul's main research interests include Symbolic and Algebraic Computation (SAC), polynomial factoring and GCD algorithms, automatic code generation, Internet Accessible Mathematical Computation (IAMC), enabling technologies for and classroom delivery of Web-based Mathematics Education (WME), as well as parallel and distributed SAC. Paul has made significant contributions to many parts of the MAXIMA computer algebra system. See these online demos for an experience with MAXIMA.

Paul continues to work jointly with others nationally and internationally in computer science teaching and research, write textbooks, IT consult as sofpower.com, and manage his Web development business webtong.com

.jpg)

.jpeg)